Walter B. Levis

Author Interview - Walter B. Levis

Author of The Meaning of Murder

The father of a modern orthodox Jewish family works as a compliance officer at a bank in New York. When he discovers that his bank is violating OFAC laws and funding terrorists in the Middle East he alerts the bank's top brass. They ignore him. After struggling with the conflict between his position as a fully assimilated member of his professional community and his moral obligations as a man and a Jew, he turns whistle-blower and goes to the DOJ. The night before his deposition he disappears.

Eliana Golden was thirteen when her father disappeared. Years later, after surprising her family by joining the NYPD, Eliana meets a mysterious and alluring soldier, a man who is far more dangerous than Eliana-and everyone except those at the highest and most secret levels of the U.S. government-understands. And he knows exactly what happened to her father.

What follows is a journey into the darkest depths of America's covert war against terrorism and the horrific moral compromises it can entail.

The Meaning of the Murder is a psychological drama and a meditation on the moral ambiguity of violence, telling the multi-layered story of a family recovering from trauma, a detective determined to solve a crime, and the price we pay for safety in the war on terror.

Author Interview - Walter B. Levis

Author I draw inspiration from:

There are so many authors who inspire me that choosing just one would distort the full picture. For me, books are like food—you need a balanced diet.

A master like William Faulkner is one of the essential nutrients, so to speak. His ability to penetrate the mysterious inner life remains unmatched. ABSALOM, ABSALOM! continues to be a touchstone for me, even with its famously challenging style.

At the other end of the spectrum, I find the well-crafted plots of popular writers like John Grisham and Gregg Hurwitz equally essential. THE FIRM and ORPHAN X are, in their own way, tremendous achievements—precise, propulsive, and deeply satisfying.

Then there’s the question of subject matter. The Jewish American experience is the story I was born into, and that makes writers like Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, and Jay Neugeboren especially meaningful to me.

But I think it’s important to distinguish between inspiration and identification. I don’t identify closely with any single writer, in part because I find myself suspended—sometimes uncomfortably—between “genre fiction” and “literary fiction.” That tension shapes how I write, and how I read.

And to be honest, some of the deepest wells of inspiration for me come not from fiction at all, but from thinkers—people such as Carl Jung, Marie Louise Von Franz, Paul Tillich, and Abraham Joshua Heschel, among many others. They aren't "authors" in the traditional sense, but their ideas have had a profound influence on me. Reading philosophy and theology hasn’t necessarily taught me how to write novels—but it has made me want to try.

Author Interview - Walter B. Levis | Author I Draw Inspiration From

Favorite place to read a book:

I will read anywhere. Living in New York City, that means subways, buses, coffee shops, restaurants, cabs, and while standing in long lines. For me, learning to read anywhere has been a necessity—I trace it back to my years pursuing a career as a tennis pro, when I had to juggle my high school and college homework with an absurd schedule of morning workouts, afternoon workouts, and way too many hours on buses traveling to matches. Back then, I’d sometimes read in the locker room. The guys on the team teased me, but I’ve always had this crazy ability to hyper-focus. I was never formally diagnosed with anything, but it can get a little weird. I mean, I’ve been known to take a book into the bathroom and forget to come out. An hour later, someone’s knocking, and I’m still turning pages. No, the bathroom isn’t my favorite place to read—but...

Book character I’d like to be stuck in an elevator with:

My choice is to be stuck in an elevator with Raskolnikov, the protagonist in the classic Russian novel Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevski. How would the scene play out...?

The lights flash. The elevator lurches. Then everything goes still.

I look at the man standing next to me. He wears an old dirty coat. It smells musty and fits poorly. He is tall, pale, gaunt—his face twitches.

“I think we’re stuck,” I say.

He doesn’t answer. Instead, he turns away from me. Then he wraps his arms around his elbows, as if he were giving himself a hug—or just holding himself together.

“You OK?” I ask.

“No, not really,” he says, keeping his back to me. “I killed someone.” His voice is flat and thin. Not a confession—just a fact dropped into the air like a coin into deep water.

I’m shocked, of course, and frightened. But I don’t feel like I’m in any real danger. I want him to tell me more.

After a moment, he turns around and looks at me and whispers, “Do you want to know why?”

Author Interview - Walter B. Levis | Book Character I’d Like to be Stuck in an Elevator With

The moment I knew I wanted to become an author:

One night when I was fourteen, I smoked so much marijuana that I thought I was going insane. “High” doesn’t begin to describe it. My mind flared at every stimulus—a sound, a thought, a streetlight, a single word. Everything felt alive and connected, swirling with layered meanings. At one point, I stood in front of a STOP sign for nearly an hour, repeating the word, wondering if “stopping” was a kind of dying.

Later, I told my friends I could feel the vibration of powerlines running beneath the street. They were frightened. In those days, I lived in the suburbs of Chicago, and one friend walked with me along the beaches of Evanston until I was calm enough to go home.

That night, I went up to my room, took out a yellow legal pad, and started writing. I didn’t craft a story—I simply recorded what I had experienced. But it soothed me. It helped me find meaning. And it revealed something crucial: the power of words.

It wasn’t until college, when I read George Eliot’s Middlemarch, that I began to see how raw experience could become literature. Eliot’s narrator writes: “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel's heartbeat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.”

That line felt like the other side of my teenage night. It made me see that writing could be more than a way to cope with being overwhelmed—it could be a way to embrace ordinary life and appreciate the mysterious power beneath the surface.

Hardback, paperback, ebook or audiobook:

This question speaks to something fundamental: our archetypal need for stories. The technology, the format, the presentation changes—but the need remains. We must have stories.

On one level, it matters little whether a story comes in the regal binding of a hardcover, with fine pages and an elegant font, or whether there’s no book at all and we simply listen to words without holding or seeing anything. What matters is that we experience the story—whether it’s a mystery, or a romance, or something more abstract like the story of an idea, or how something works.

Stories involve meaning—and meaning is something we experience with our whole selves. In that sense, reading is like exercising. The formats—hardback, paperback, ebook, audiobook—are like the differences between jogging, swimming, cycling. The methods vary, but they all get your blood flowing.

Personally, I find the audiobook fascinating because of its paradoxical nature. It’s arguably the most recent innovation in how we “read”—but for me, it also feels like a return to our earliest way of sharing stories. Long before there was writing, there was the spoken word. A well-read audiobook can be incredible.

A recommendation: Meryl Streep reading John Cheever.

The last book I read:

I’m always reading more than one book at a time. It’s the balanced diet idea—reading only one book would be like eating only one food group. But for the sake of brevity, I’ll focus on the last crime novel I finished.

DARK RIDE by Lou Berney is the story of a young man drifting through his early twenties who notices two children with suspicious burn marks. When his attempt to involve child protective services goes nowhere, he takes matters into his own hands. What follows is part thriller, part moral reckoning—a quest for justice for the children, and a journey of self-discovery for the protagonist.

What struck me most, beyond Berney’s masterful use of suspense, was his point of view choice. The story is told in the first person present tense. The opening line is: “I’m lost, wandering, and somewhat stoned.” The narrator tells the story as it happens—there’s no interpretive distance, no hindsight. He will tell us what happens—as it happens. Play by play, so to speak.

This stands in sharp contrast to, say, The Great Gatsby, which famously begins: “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since.” Fitzgerald gives us a narrator who’s looking back, processing the past through the lens of experience and regret.

There’s no single “correct” point of view, of course—but in Dark Ride, the immediacy of the first-person present tense places us deep inside the protagonist’s emotional and moral world. It’s like watching someone cry in front of you, rather than hearing about their tears a few days later. One is raw and inescapable; the other more thoughtful and processed.

I don’t know if Berney made that choice consciously. To a reader, it doesn’t really matter—it works. But for me, as a writer, it’s like hearing a jazz solo that sounds effortless, then going back to study the structure underneath and discovering its technical brilliance. Appreciating the narrative choices in Dark Ride reminds me to think hard in my own work about how point of view shapes emotional impact.

Author Interview - Walter B. Levis | The Last Book I Read

Pen & paper or computer:

Pen, paper, computer, iPhone, audio recorder—I’ll use any and all of them, as often as I can. In Saul Bellow’s first published novel, Dangling Man, the narrator is desperate to express himself. He says: “If I had as many mouths as Siva has arms and kept them going all the time, I still could not do myself justice.” That line has always stayed with me, because I often feel the same way when I try to turn thoughts and feelings into sentences. If only I could write two paragraphs at once—one with each hand.

But behind all this is a serious question: how does one commit to the process of writing? For me, the commitment has meant finding ways to write no matter what else is happening in my life—earning a living, raising a child, caring for an elderly parent, trying to be a halfway decent husband. The key has been learning to work in short bursts: thirty minutes before bed, fifteen minutes in a doctor’s office, or—one of my favorites—forty minutes on a bus from the Bronx to Manhattan. I used to joke that I was the only guy on the Major Deegan hoping for a traffic jam.

Yet I don’t want to joke too much. Writing in short bursts is only part of my process. I’ve also binge-written, sitting at my desk for twelve-hour stretches straight through the night, barely registering the passage of time. And, to be totally honest, I’ve struggled with the role of alcohol in all this.

Ultimately, what I think matters most is achieving a state of mind where it’s okay to explore an idea or feeling without knowing where it will lead. It’s been said that art is “serious play.” I like that phrase because play suggests the innocence of childhood, when openness, spontaneity, and improvisation come naturally, without judgment.

When kids play “let’s pretend,” they say, “You be X, and I’ll be Y,” and then the game unfolds. In a sense, children are first-rate improvisers. Adults, however, learn to be serious—and that’s part of maturation. I think writers should take themselves seriously, but we also need the absolute freedom of child’s play.

The challenge is to embrace the tension of this paradox.

Whether the words begin in an audio file or on a scrap of paper, once there’s the seed of an idea, the rest of the process demands something that I think serious writers share with just about everyone, not only so-called “creative people.” What I mean is: simply trying to live a full and authentic life requires stepping into the unknown, and finding in ourselves the courage to take a chance and fail. And then doing it again, and again.

Book character I think I’d be best friends with:

I’d like to be best friends with Hanson, the protagonist in NIGHT DOGS, by Kent Anderson, a writer whom Michael Connelly once called “the best of the best in American storytelling today.” Hanson is a military veteran who becomes a police officer. My new novel explores a relationship between a soldier and a cop, and I’m drawn to the complex distinction between criminal violence and political violence. I’m also interested in the struggle to maintain our humanity as the world becomes more and more dangerous—and violent. Hanson embodies these themes not abstractly, but viscerally.

At the start of the book, as he responds to a radio call, we learn that he is wearing a yellow “happy face pin” just above his gold police badge.

He’d picked up the pin back in December, off the body of a kid who’d OD’d in a gas station bathroom, sitting on the toilet. The needle was still in his arm, half-full of the China White heroin that was pouring in from Southeast Asia, through Vancouver, B.C., and down the freeway.

Hanson thinking about the drug route marks the first of many times he will reflect back on his experience of Southeast Asia, where he served during the Viet Nam War. Later in the same scene, while his partner, Dana, starts their investigation, Hanson notices a hedge of rose bushes.

Dana, the big cop, knocked on the door with his flashlight and shouted, “Police.” Hanson picked up a rose petal, smelled it, then put it on his tongue. “Police,” Dana shouted again.

This gesture with the rose petal defines, for me, what makes Hanson such a compelling character. Amidst the police work, he doesn’t just “stop and smell the flowers,” as the saying goes. He puts the rose petal on his tongue. As the story of Night Dogs unfolds, we learn that Hanson is, indeed, a man deeply initiated into the horrors of violence, but he is much more than that too. He is a man who refuses to let go of beauty, absurdity, and tenderness, even when the world gives him every reason to.

Author Interview - Walter B. Levis | Book Character I’d be Best Friends With

If I weren’t an author, I’d be a:

In my dream career, I’m a first-rate jazz guitarist performing in the most renowned clubs in the world. In reality, I’m a dedicated amateur playing in nursing homes, street fairs, restaurants, and community events around the Bronx.

I come by my love of music honestly. My mother was a music teacher who gave piano lessons for four dollars an hour. I remember her coming home with her coat pockets stuffed with crumpled singles. For some reason, she never folded the bills—my job was to straighten and stack them. My father showed me how to run a bill back and forth along the kitchen table to smooth out the wrinkles. Our house was always filled with musicians; in addition to teaching piano, my mother played chamber music, and people were constantly coming and going.

So why didn’t I become a professional musician? It’s complicated. It has to do with the idea of pure, raw talent. As a teenager, I’d been a serious tennis player with dreams of Wimbledon. The closest I came was a number seven ranking in Illinois’s 18-and-under division, and a scholarship to play in the Big 10.

That’s when I began to see the limits of effort. No matter how hard I practiced (and I was known for practicing hard), some athletes were simply bigger, faster, and better. I projected that same model onto music—mistakenly, as I later realized. The analogy between athletics and the arts is imperfect, and I pushed it too far.

At the start of my senior year in college, I quit the tennis team and dropped out of school to do nothing but study guitar with the renowned Roy Plum, a disciple of none other than Andrés Segovia. I practiced hard and learned quickly, soon performing at local venues. But I still measured myself the same way I had as an athlete. I wasn’t a prodigy. I wasn’t going to be a master. So what was the point? I quit the guitar, went back to school, and began to take myself seriously as a writer.

I didn’t pick up a guitar again for twenty years. But when my daughter was little, I wanted to be able to play songs for her—a modest, personal goal. So I found my old guitar and strung it. Gradually, I started playing more and more, eventually taking lessons with Carl Berry, a little-known but brilliant jazz guitarist in New York City.

It was Carl who changed my attitude. I’ll never forget the moment. I was deep into a lesson, frustrated over a technical challenge, and really getting down on myself. Carl leaned forward, put his hand on my shoulder, and said: “Listen to me. You’re confusing technical virtuosity with musical expression. Stop measuring yourself against some abstract idea of success. Play the song with sincere feeling, with the goal of reaching other people. That’s what music is about.”

Carl’s words marked the beginning of giving myself permission to play music in community settings, which remains an important part of my life. And his insight extends to my writing as well: to write with sincere feeling, with the goal of reaching other people—this has always been my true intention.

But it’s not always easy to hold.

Ezra Pound, who helped define Modernism as an art movement, famously declared, “Make it new,” a rallying cry for writers to break away from tradition and innovate in both style and form. That call can feel to me like a demand for technical mastery—the literary equivalent of musical virtuosity.

In contrast, C.S. Lewis once wrote: “Even in literature and art, no man who bothers about originality will ever be original: whereas if you simply try to tell the truth (without caring two-pence how often it has been told before) you will, nine times out of ten, become original without ever having noticed it.”

The tension between these two views is real. For me—as with so many aspects of writing—the only authentic response is to embrace the tension between them. And authenticity: that word has become a crucial touchstone. It carries within it the same origin as “author,” a connection reminding us, perhaps, about the deepest meaning and value of writing.

Favorite decade in fashion history:

I’ve never paid much attention to fashion in the traditional sense—trends, designers, decades. But I do pay attention to people. There’s a quote often attributed to the great jazz bassist and composer Charles Mingus: “A man is a genius just for looking like himself.” That resonates with me more than anything I could say about a favorite fashion era.

For a while, when I worked as a tennis pro, I ran a small shop connected to the club. Members would come in and spend serious money—sometimes hundreds of dollars—on the newest shirts, skirts, or branded gear, hoping the right outfit might somehow improve their game. They would walk out onto the court looking great, but still gripping their racket like a frying pan.

I can’t name a favorite fashion decade, but I notice the small, telling choices: a frayed collar, a perfect crease, a jacket worn past its prime. As a writer, I think about what clothes reveal—and what they conceal—and how much of our identity is wrapped up in what we put on in the morning. It’s a question of how we present ourselves.

Maybe the opposite of choosing your clothes for fashion is having them chosen for you—by an institution. In my volunteer work as an Auxiliary Police Officer, I’ve had firsthand experience of the power of the uniform. In New York City, Auxiliary Officers wear nearly identical uniforms to regular officers, with only small distinctions in our patch and badge. We don’t carry firearms, but we do wear duty belts with radios and handcuffs, and we wear ballistic vests like regular officers. Most civilians don’t notice the difference. The way people interact with you when they think you’re a cop is fascinating. I’ve had people thank me for being present at a bank or subway entrance purely because they see the uniform.

Once, while stationed outside a synagogue, a longtime neighbor looked me right in the face and didn’t recognize me. She simply saw “a cop” and said,Thank you for being here. She wasn’t thanking me—she was thanking the uniform. I saw no reason to identify myself; it would just spoil the moment. In that sense, the old saying was completely true: “The clothes make the man.”

Place I’d most like to travel:

I’m not much of a traveler. Years ago, my wife and I went camping in the White Mountains of Vermont—a full week in the woods. It was hard for me. The woods get very dark. And at night, there are strange sounds. People who knew me were surprised I had taken the trip.

“Wow,” they said. “I didn’t know you liked camping.”

“I don’t,” I said. “I don’t like camping. I don’t like it at all. The woods are where animals live. People live in cities. But my wife, you see—she loves camping. And I love my wife.”

Eventually, my wife and I worked out this small issue. And, of course, one can travel and stay out of the woods. There are cities to visit. The one on my mind right now is Jerusalem. In fact, I have a plan to visit Israel in September 2025 as part of a trip organized by the NYPD and the national Shomrim Society, the fraternal order of Jewish police officers. As an Auxiliary Police Officer, I’m a member.

Why visit Israel, especially right now? I don’t have an easy answer to that. I’ve never been there before. I’m Jewish, yes, but I never had a bar mitzvah and don’t speak Hebrew. I have no formal religious training at all. Still, I feel connected to what is happening there—and that connection is not simple.

My novel explores this complexity—call it the condition of the Diaspora Jew, or the question of what feeling a sense of moral obligation means when you’re trying to live a normal life. In the story, the father of a modern Orthodox Jewish family works as a compliance officer at a bank in New York. When he discovers the bank is violating OFAC laws and funding terrorists in the Middle East, he alerts the top brass. But they ignore him. His wife, who fears retribution, urges him to let it go. But he turns whistle-blower and reports the bank’s violations to the Department of Justice. The night before his deposition, he disappears—leaving behind his wife and three daughters.

Years later, Eliana Golden, the middle child—who was thirteen when her father vanished—surprises her family by joining the NYPD, where she continues to investigate his disappearance. Eventually, she meets a mysterious and alluring soldier, a man far more dangerous than she—or anyone outside the highest levels of the U.S. government—understands. And he knows exactly what happened to her father.

Eliana’s journey forces her to confront not only the horrific moral compromises of the war on terror, but also the tangled reality of what it means to be a Jew in America today.

So, why visit Jerusalem? I think I’m drawn because, in some way, it feels like the ultimate ground zero—for faith, for identity, for the unresolved contradictions that shape my characters and, I suspect, my own life too.

My signature drink:

The truth is: I’ve struggled with alcohol. So “signature drink” is a complicated phrase for me. For a long time, I would have said “Boiler Maker,” which is a shot of straight bourbon with a beer chaser. Any bourbon, any beer. The taste didn’t matter. The impact mattered. That’s why I can say with conviction: I don’t miss drinking; I just miss being drunk.

My father drank Scotch—Johnny Walker, neat, no ice, no water, just poured to the brim. I’m the youngest of four boys, and I’ll never forget how proud I was when I finally got big enough to climb onto the kitchen counter, open the liquor cabinet, and pour my dad his Johnny Walker. We didn’t use shot glasses. We used water cups—eight ounces, filled all the way.

I don’t tell this story to dramatize anything. My father was a loving man. But he was also an alcoholic. And for a while, I followed that same path. That’s another kind of inheritance.

These days, it’s all about coffee. And I figure I’m in good literary company. Hemingway drank his black and wrote standing up at dawn. Balzac downed fifty cups a day and worked through the night, eventually writing ninety novels—by hand. Sartre combined coffee with amphetamines to fuel marathon writing sessions. He considered drowsiness a kind of existential lapse. Eventually, he began hallucinating that a lobster was following him around Paris.

I admire these literary lions, but my coffee drinking is much simpler: a nice full mug to mark the start of the day, and another to keep me going in the late afternoon. I like it strong, with plenty of half-and-half.

I suppose the most important thing—for me—is just to drink on my own terms. Something I think my father would understand.

Favorite artist:

I don’t have a single favorite artist. But there are a few whose work feels personally meaningful to me—artists whose images I return to, not just with admiration, but with a kind of emotional recognition. At the top of that list is Marc Chagall.

Chagall was born in Russia in the 1880s, lived through both World Wars, and continued making art well into his nineties. His work spans many forms—painting, stained glass, illustration—but what stays with me most is the mood: dreamlike, poetic, and somehow deeply human. My wife and I chose one of his paintings for the cover of our wedding invitation. It’s not one of his famous bridal couples, but a quieter image: a man and woman kissing, the woman holding flowers, the man floating above her, both of them tilted at impossible angles, their eyes locked on each other.

The picture resonated with us for several reasons. Both our families have roots in Eastern Europe. We also recognized something familiar in the sense of longing and weightlessness, the intimacy and strangeness. Chagall’s work often feels like a kind of visual reverie—whimsical, figurative, sometimes upside-down, his images arranged almost arbitrarily, as if memory and imagination were spliced together like a film montage. The mood shifts easily: a Yiddish joke, a Russian fairy tale, the ache of a half-forgotten dream.

His way of seeing—fragmented, dreamlike, emotionally charged—has stayed with me. In my new novel, although there is a crime and a mystery at its center, I’m also trying to evoke that sense of interior collage: memory layered with myth, history mixed with longing, reality refracted through feeling. Chagall doesn’t try to make the world logical. He just tries to make it felt. That, to me, is a kind of truth worth chasing.

Number one on my bucket list:

I’ve never liked the idea of a bucket list. I’m not sure why. Maybe it’s the image of life as a to-do list—one more set of tasks to check off before the end. And I say that as a compulsive list-maker. I write daily to-do lists, I rewrite them, I add things after I’ve already completed them, then cross them off just to feel a sense of forward motion. But somehow, the phrase “bucket list” leaves me cold.

The truth is, I’ve spent most of my adult life writing and working at the same time. First, there were the tennis pro days. Six, eight, sometimes ten hours on the court—then the welcome relief of the chair at my desk. Next came journalism. Juggling assignments, interviewing sources, editing stories, chasing ideas. I’d come home after a full day and still want to write—what I called “my own stuff.” Short stories, plays, novels. That desire never went away.

Later, I freelanced—ghostwriting speeches, crafting ad copy, writing annual reports—saying yes to whatever paid. Eventually, I became a teacher. I taught Writing, English, History, and a set of electives with titles like Money & Morals, Sports Ethics, and Contemporary Moral Problems. Teaching never stops. Grading papers is a Sisyphean task, but so is preparing for class. And still, through it all, I never stopped writing.

But let me elaborate slightly on what I mean here. When my schedule was at its absolute busiest—raising a young child, caring for elderly parents, working a full-time job—I permitted myself to say that if I moved a story or novel or essay forward by a single sentence—yes, just one sentence—I could go to bed that night and tell myself, “Yes, I wrote today.”

The Nobel Prize–winning novelist Saul Bellow, one of my literary heroes, once said: “To be a writer one learns to live like one... The main business is to find the most appropriate and stimulating equilibrium.” For most of my life, that equilibrium meant writing while working. But now, for the first time, I’m not earning a living some other way. I’m just writing. (Although, to be totally clear, my modest earnings as a musician are still part of the family budget.)

So no, I don’t have a bucket list. What I have is a kind of young-guy ambition that’s a little embarrassing to admit. Can I still write the Great American Novel? OK—maybe that’s too grand. And in today’s fragmented world, I’m not even sure such a thing exists.

But I would like to take Bellow’s advice—to find the most appropriate and stimulating equilibrium—and write the book my whole life has prepared me to write. And then write another.

Or maybe there’s another possibility altogether. This one comes from a dream I had: I’m at a funeral. There’s an open casket. I look down into it and see that I have died. It’s a very strange sensation because I know that I also remain alive. Then I look more closely into the casket and see that objects—votives—have been arranged along the side of the body. There are yarmulkes, and a tallis, and silver wine goblets, but it’s mostly books, many from my own waking-life bookshelves: a few hardback versions of the Torah, the works of Bellow, Carl Jung’s COLLECTED WORKS, Mordecai Kaplan’s JUDAISM AS A CIVILIZATION, and Martin Buber’s I AND THOU. I realize that these books are being buried with the body, and although I don’t understand it completely, I know that it’s a ritual of deep spiritual significance. Then I woke.

Dream interpretation is, of course, an ancient art. How I understand this one is that something in my dedication to writing has been transformed. In one sense, it has died; yet at the same time, it survives.

Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to crime fiction. There’s a mystery here.

Anything else you'd like to add:

I’m new to this format—the blog-written-interview—but I like the idea behind it. Amidst the overwhelming amount of content online covering every possible subject, it’s reassuring to know there are sites like this one dedicated to people who care about new books. I’d like to believe we’re keeping alive the quiet art of reading and writing. I feel lucky to be part of it. Thank you.

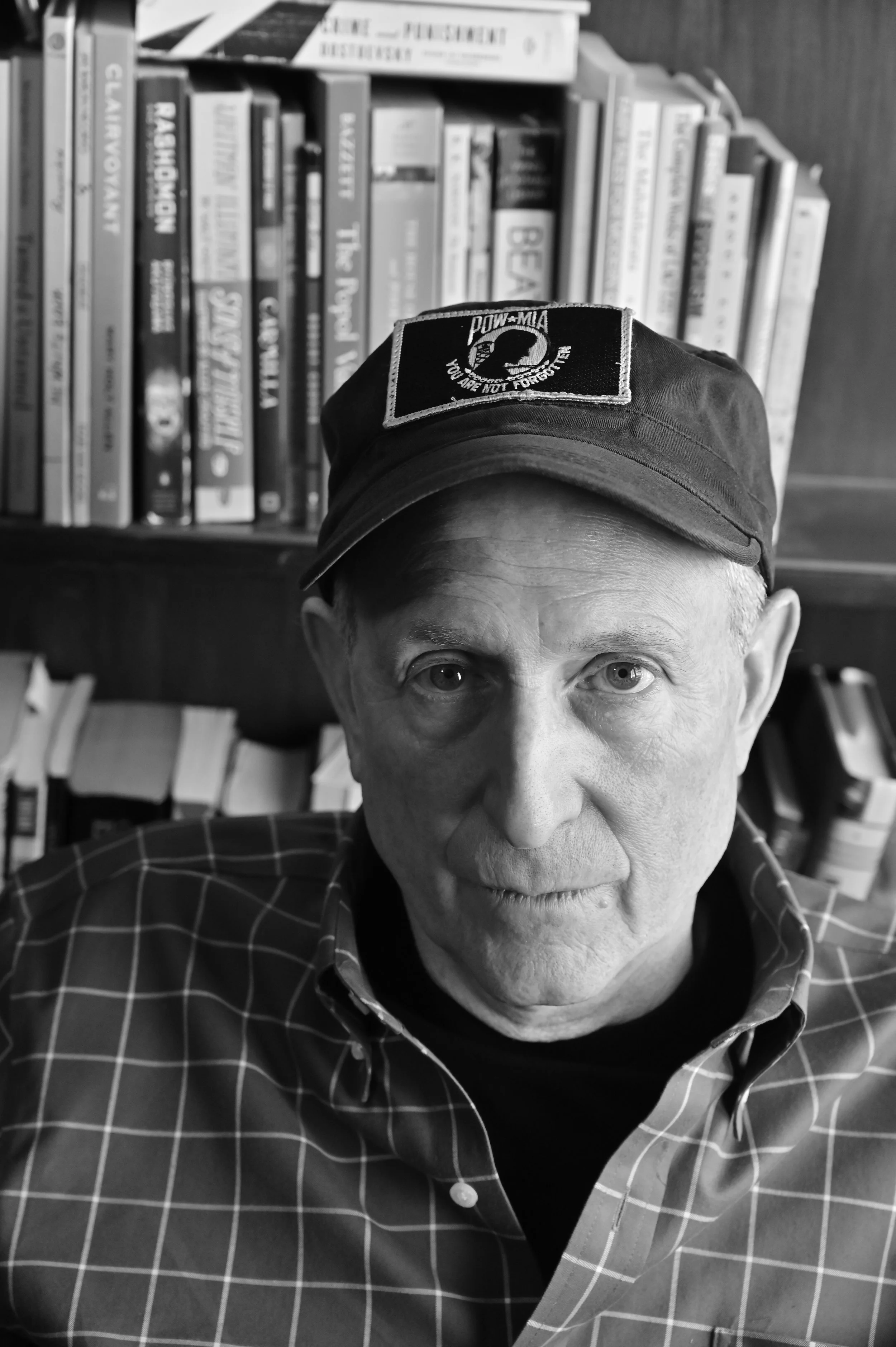

About Walter B. Levis:

Author Interview with Walter B. Levis

A former crime reporter, Walter B. Levis’ work has appeared in The NY Daily News, The National Law Journal, The Chicago Reporter, The Chicago Lawyer, The New Republic, Show Business Magazine, and The New Yorker, among other publications. He is author of the novel Moments of Doubt. His short stories have appeared widely, and have been chosen for a Henfield Prize and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His new novel, The Meaning of the Murder, will be published in 2025 by Anaphora Literary Press. For 17 years he taught at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City. Previously, he served as a Dean at Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School.